In many ways, the Reformation was not merely a change in the religious landscape, but also a renovation of the entire social order. Economics were impacted, education swelled, and the missionary impulse brought Europeans into increasing contact with other cultures - and conflict with other Europeans. Great was the turmoil and many the monstrous crimes committed in the name of Christ in the wake of the Reformation. Religious passions quickly passed into political conflict. No place was this more true than in Germany, where peasants rioted at the behest of the radical Anabaptists. And, of course, Luther's alliance with certain Prince-Electors was a sore spot for the Roman Catholic aligned Holy Roman Emperor, Charles V.

At the Diet (a formal assembly of princes) of Worms in 1521, Emperor Charles V outlawed Lutheranism . But he was unable to stamp out the reform movement at the time because of other crises. Not until 1529 was Charles able to follow up on the Lutheran issue. He sent word that Catholicism was to be restored everywhere in Germany. Many German cities and princes protested. These were called the "Protesting estates" and from them we got the name "Protestant."

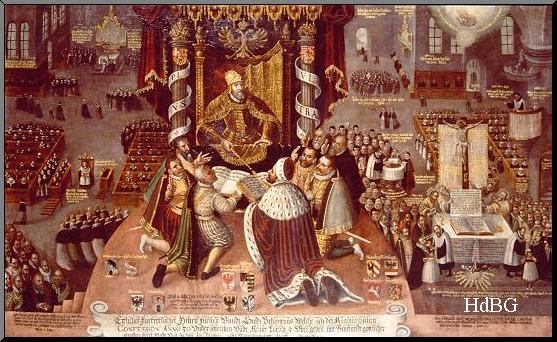

Charles saw that some sort of conciliation would be in order. In 1530 he attended an assembly known as the Diet at Augsburg.

Lutherans presented the Confession of Augsburg (authored principally by Philip Melancthon) in an attempt to prove to Rome that their views were Biblical. This confession remains the basis of the Lutheran faith. However, reconciliation proved impossible and Charles ordered Lutherans to reunite with the Catholic church by April 15, 1531. This had the effect of stiffening opposition against him. A military alliance of Protestants, known as the Schmalkaldic League came into being. Charles crushed this, but Elector Maurice switched sides and declared war on the emperor, forcing him to negotiate with the Protestants. In 1552, at the Peace of Passau, Charles accepted the existence of the evangelical church and promised to hold a "diet" to settle the controversy.

The diet was not convened until 1555. Again it was held in Augsburg. Peace was arranged between the Lutherans and Catholics on this day, September 25, 1555. In many respects it was imperfect. Although Lutherans were given legal standing, Anabaptists and Calvinists were not. "[A]ll such as do not belong to the two above-named religions shall not be included in the present peace but be totally excluded from it." Each German territory must take the faith of its prince. This inbuilt religious divisiveness crippled Germany's ability to unite as a nation. There was no toleration within a territory.

The Peace of Augsburg did, however, permit people to transplant to a region whose faith was more congenial to each. "In case our subjects, whether belonging to the old religion or to the Augsburg Confession, should intend leaving their homes, with their wives and children, in order to settle in another place, they shall neither be hindered in the sale of their estates after due pay, net of the local taxes nor injured in their honor... "

The Peace of Augsburg offered the merest hint of toleration. Weak as was the treaty, it brought increased stability. However, not until the Peace of Westphalia in 1648 were Calvinists added to the list of tolerated religions.

Bibliography:

- "Augsburg, Peace of." The Oxford Dictionary of the Christian Church. Edited by F. L. Cross and E. A. Livingstone. Oxford, 1997.

- Durant, Will. The Reformation; A history of European civilization from Wyclif to Calvin: 1300 - 1564. The Story of Civilization, Part VI. New York: Simon and Schuster, 1957.

- Kidd, B. J. Documents illustrative of the Continental Reformation; edited by B. J. Kidd. Oxford, Clarendon Press, 1967.

- Simon, Edith and the editors of Time/Life. The Reformation. Great Ages of Man. New York: Time Inc., 1966.

- Various encyclopedia articles & websites.

No comments:

Post a Comment